In my last post I checked in on my progress learning Japanese after 3 years. This one talks more about what I actually learned. Learning Japanese hasn't just taught me a lot about Japanese, I've also learned a lot about the art of learning a language.

I believe the act of language learning is itself a 'meta skill' - you can get better at the act of learning languages generally, separate to your skill level in any specific language. This post talks through some general ideas that I've picked up over the last two years that come under that meta-skill of learning languages.

If I had to sum up the theme of my learning in one word it would be 'context.' You're going to see that idea many times below as I walk through two handfuls of different concepts that I've picked up over the years and that form the foundation of my study right now.

Language Learning Concepts

1. Comfort With Ambiguity

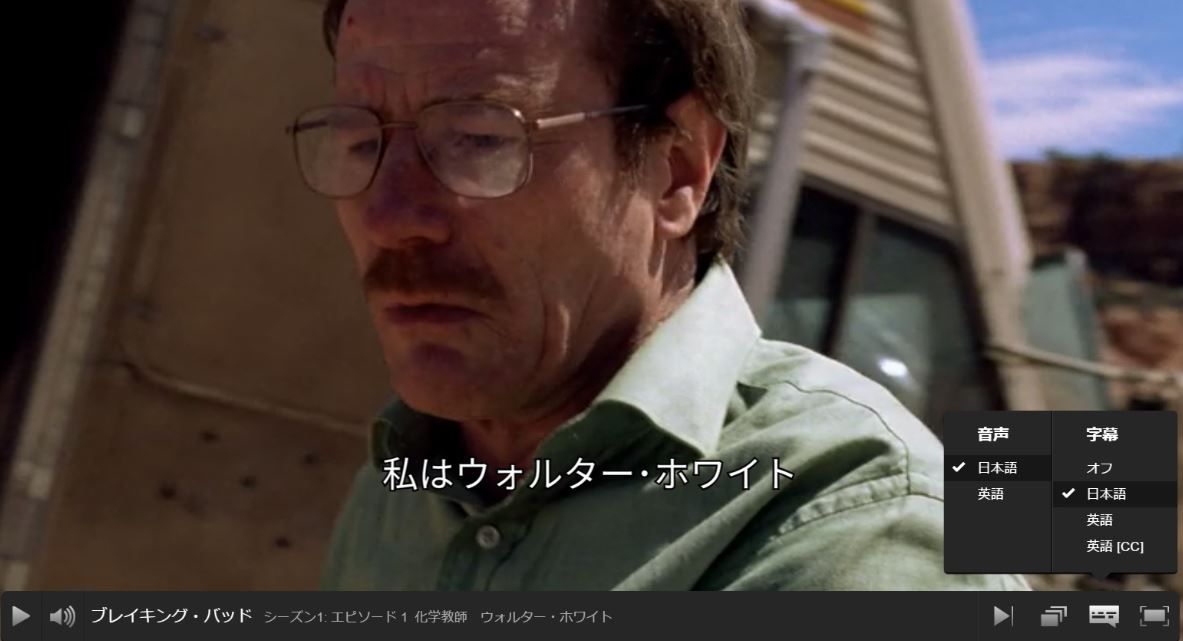

I didn't immerse much in TV/Anime and reading until about 9 months ago. This was a mistake. I was fixated on knowing enough to understand everything, and I wanted to make sure I had all the vocabulary I needed to understand an episode of TV before I watched it. When I did occasionally try to watch something, I got frustrated at encountering so many new words, thinking 'well, I guess I just need to study more' and going back to the textbooks. I didn't like the feeling of discomfort that comes with not understanding.

In hindsight, I focused too much on following my textbooks and could have tackled this much earlier if I was more comfortable with ambiguity. I had it ass-backwards - you don't learn words and grammar until you reach some magical point where suddenly you understand what you're watching. You watch something - even if you only understand 30% or less - puzzle out as much as you can, and your brain just puts together the pieces and intuits the meaning of new words over time, until eventually you get to full comprehension. The very feeling of discomfort which I was trying to avoid is integral to the process of learning.

As an analogy, think of learning an instrument, say piano. You don't replay 'chopsticks' over and over again until suddenly you can play fur elise. You constantly keep stepping up the difficulty, struggling at harder and harder pieces until eventually you get there. Languages are also like this, you have to put yourself into situations where your brain can understand enough to not switch off totally and stop paying attention1, but challenging enough that you're forced to engage fully to try to make out the words and meaning.

Don't put off watching TV, etc in the hope you'll reach some magical level where you suddenly have full comprehension. Immerse early and often, turn off the subtitles (or watch it with subtitles the first time and then drop them on repeat viewings), and try to follow along with whatever you're watching. One word and phrase at a time, your brain will figure it out. This doesn't mean textbooks and vocab lists shouldn't be used - they're a handy shortcut to bootstrap yourself from 0% comprehension - but you can't expect them to be any more than a shortcut that allows you to get into the real meat of immersion faster.

2. Critical Mass

The most satisfying period in my language learning journey was when I hit 'Critical Mass' in my knowledge of Japanese. By this, I mean the period when I went from everything being new and needing to be looked up, to having enough knowledge to figure things out from context. I'll illustrate with an example.

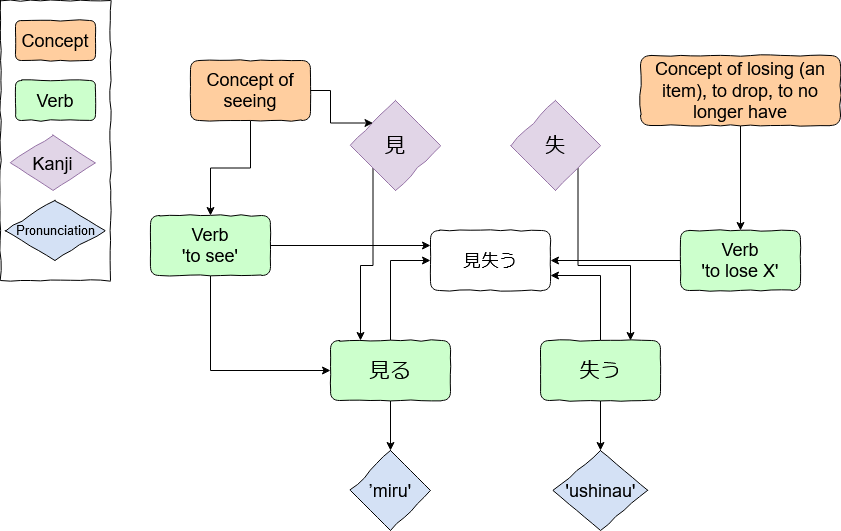

I like to think of the knowledge in my head as a 'Language Web' of interconnected pieces of information, something like the picture above. It seems to me like the actual way we learn a language, each new word connecting to similar related words, symbols and concepts. The beauty of having this 'web' of knowledge is that eventually, you build up enough bits and pieces that you can see a totally new word and, without needing to actually look up the word, intuit it's meaning and pronunciation. 見失う in the diagram above is an example of a word I had this experience with. Based on what I already knew I could figure out, without specifically learning the word, that it was pronounced 'miushinau' and means 'to lose from sight'

Reaching this critical mass of existing knowledge is fantastic because your knowledge becomes self reinforcing - you no longer need to look up every word, and it stops feeling like a slog to keep building that Language Web one piece at a time. Instead your brain is filling in gaps on its own. You can watch/listen/read media that you don't yet have full comprehension of and trust that you'll usually be able to figure it out by yourself.

3. Domain Specificity

One of the things that I had to get over in order to progress was staying inside my 'domain-specific' comfort zone.

What do I mean by domain-specific? Well, imagine most of your immersion comes from watching anime. You do this as you study, eventually getting to a point where you're very comfortable watching and understanding anime without subtitles. Sometimes you finish watching an episode and in the moment you click next you realise that the entire thing was in Japanese, without subtitles, and think to yourself 'This is awesome, my Japanese is great!'. What do you think happens the first time you try to watch a news report? Zero points for guessing right - It sucks! You understand almost nothing because the way of speaking, the vocab, everything is entirely different. I experienced this roller coaster of self confidence as I learned; I had days where I would chat for hours with a friend over a coffee, feeling really chuffed at how far I'd come, then other days where I struggled to follow along and felt like I knew nothing. This was because I had practiced heavily in some domains and not others.

The takeaway here is to know ahead of time, in any new language, that you're only going to be able to understand what you practice understanding. You will feel stupid the first time you try to make a phone call related to making an appointment, or inquiring about a phone bill, etc, because you've never done it before, even if you've studied the language for years. Knowing this ahead of time, you can make a conscious effort to add new 'domains' to your fluency, and be prepared for and embrace that feeling of being a total beginner any time you do something new.

4. AJATT/MIA

I came across AJATT (an acronym that stands for 'All Japanese All The Time' and originates here) and MIA (The Mass Immersion Approach) about 2 years into my study and I wish I'd found it earlier. If you're reading this post with the intent to learn Japanese, I highly recommend following the Mass Immersion Approach. You can start with the MIA Primer plus the Youtube Channel. The complete philosophy is more than I have time to cover in one post and has already been covered in depth by multiple people, but the essence of it is this:

The only way to truly internalize and understand a language is with a massive2 amount of immersion. This is especially true of Japanese because Japanese is so different from western languages, but it applies to every language. Think of how you learn a language as a child. You don't sit down and open up a dictionary every time you encounter a new word - unless you were a really weird 2 year old. Instead, your brain just figures out the meaning of new words through encountering the word hundreds of times, in contextual, correct, sentences. You observe and listen and eventually your brain just kind of 'gets' that this word is used in these contexts in these ways. This is what you have to do when learning a language as an adult too. Textbooks and vocab lists and English translated definitions are just a kind of 'shortcut' so that you can remember that word XXX roughly means YYY and not be totally lost when seeing it in the wild. But as for the precise meaning and usage of XXX, it's only after seeing the word used tens and hundreds of times that you'll really internalise what it means.

5. Languages Aren't One-to-One Equivalent

The fact that we already speak one language is something of a blessing and a curse. It's a blessing because you can look up the meaning of new words in your native language and use that as a starting point to have a vague idea of what the word means. You still need to hear it used hundreds of times in different sentences to truly internalize the meaning, but you get a head start from the definition. But it's also a curse because you can latch onto the translated meaning and use it the wrong way, repeatedly, until one day you hear a sentence that doesn't jive with the meaning in your head and realize you've gotten it wrong. Having this happen to me countless times is part of what sold me on the MIA/AJATT philosophy, as this basic explanation - you cannot directly translate the meaning - explained exactly the problem I was encountering. Note that this applies less to the romance languages3 which are so close to English that often they do have exact 1-1 translations.

Let me illustrate with an example: the word 分解 (bunkai), which in a Japanese to English dictionary is defined as "disassembly; dismantling; disaggregating; analysis; disintegrating; decomposing; degrading". As a native English speaker, you know that those words have similar, but slightly different meanings and uses. You could say "I am disassembling this car", but it would sound wrong to a native ear to say "I am degrading this car". On the other hand you can say "rust makes iron degrade", but not "rust makes iron disassemble."

So, what does 分解 really mean? Does it mean some sort of combination or halfway point between all these meanings? Or does it have multiple meanings that are different? Are you actually going to memorise that list of English equivalents then mentally flick through them all every time you see the word? No, that's ridiculous, and it still wouldn't tell you whether it sounds natural to use when you're talking about a car or a piece of rusty metal. You have to treat that English meaning as a starting point, and only after seeing it used in a hundred different contexts will you intuitively grasp what it means, and when you can and can't use it. Going back to the analogy of a knowledge web, imagine that you've now shaded in a zone between all these points, and then each time you see the word used in the wild you can slowly narrow it until you hone in on the right place in your web.

Relatedly, the meaning of a Japanese word can be defined in the native Japanese much more precisely than in English. That's why I recommend learning new words in Japanese through a Japanese dictionary, rather than with translations from a Japanese-English dictionary. That will get you a lot closer to the correct point in your Language Web, and it will connect new nodes in the web to Japanese words instead of English ones.

6. Input over Output

Something that I got 'accidentally right' in my own studies was that I didn't even try speaking Japanese until I'd already studied for a year. Mostly this was a confidence thing; I didn't want to waste someone's time if I couldn't speak about topics more complicated than how nice the weather is today. But it turns out it's also a more productive way to study. I was reviewing my N3 books as part of my practice for N2 and noticed that I was getting questions right because some sentences just 'felt' right or wrong and wasn't able to explain why. It was something of an epiphany for me when I realized that not only is it possible to build an intuitive 'feel' for your target language, its much faster and easier than trying to 'prove your work' every time by referring the grammar rules.

So one piece of advice I'd give to anyone else studying a language, particularly ones that are linguistically distant from your native tongue, is to focus on listening and language input over language output. Don't try to generate new sentences using the grammar rules you've learned, as you'll almost always get it wrong. Grammar is too subtle and nuanced and has too many exceptions and unwritten rules for you to be able to put together a correct sentence by reasoning from fundamentals, most of the time. The reason for learning grammar rules is to help you understand, not to help you speak. This was a hard habit to break even after I did start speaking, because in math you're taught to do the opposite: learn the fundamentals and use them to derive the answer. But language is not math.

Instead, reason from correct sentences. Start with a sentence that you know is correct, because you heard a native speaker say it, then swap out words that you know are valid to swap out. If you focus on only saying things you've previously heard a native speaker say, you can have 100% confidence you're not making a mistake.

Interestingly, this means memorizing a bunch of phrases from a phrasebook is actually not a terrible way to learn a language. You'll at least know that everything you're saying is grammatically perfect, instead of having to guess whether the sentence you constructed using the grammar rules you've learned is correct.

It also means you're building an intuition for what is right or wrong in the language. As a native speaker, there are a lot of rules you don't know you know. You can tell whether something is right or wrong without referring to grammar rules. Take the sentence 'The red big dog.' As a native speaker reading this, you know it should be 'The big red dog' instead, but you've never had to learn the corresponding rule4.

Aim for the ability to do this in your target language too.

7. Opportunistic Vocab Acquisition

At some point during my learning, I transitioned into being able to get by entirely in Japanese. During this transition, I quickly came to realize that the order in which my textbook was teaching me words wasn't going to match up with the order that I was acquiring words naturally in conversation. I would be happily chatting away in Japanese and the person I was talking to would throw in a word like 地球温暖化5 or 少子高齢化6, because of current news, or a word like スマホ7 because it's a commonly used word in speech that wasn't so common when the textbook was written.

This one's going to be obvious to many people, duh, of course you need to learn words as you encounter them, but it was still something that threw me off when it happened. The solution is pretty straightforward. I keep a note on my phone 'New Japanese Vocab' and every time I hear a new word, I write it in that note. At a later date I create an entry in Anki (spaced learning app) for the new word and include example sentences.

One problem was that most of the time when I'd ask, "hang on could you repeat that?" the person I was talking to wouldn't repeat the exact sentence. Instead, they would rephrase the same idea in easier words, trying to help me understand. e.g.

"... and so by the time I got back from my trip, half the food was past its' use-by date and I had to throw it out"

"Hang on, could you repeat that? Use-by..something?"

"Oh, the food was too old so I couldn't eat it."

Often I lost the word entirely, because by the time they had repeated it in simpler vocab and I asked them for it again, they'd completely forgotten the exact word they had just used...

My process is:

- Write down new words as I notice them in the wild, from immersion or through conversation.

- Whenever I have time to learn new words, start with words that arose organically through conversation, as these are ones that I know are real words used in real situations.

- Any time I don't happen to have new words from immersion, I work through a chapter of my textbook to find them. There are many uncommon words that you might only encounter a few times each year, but are still important to know for when you do see them.

It's a more natural process where textbooks, immersion material, and everyday conversation all work in tandem to feed into your Language Web and help connect the dots between textbook Japanese and the real thing.

8. Learning New Words In Context

Many beginners start with vocab lists, and they're a staple tool of textbooks and language classes. I actually think this is a mistake, one that leads people down the path of memorizing lists of words in isolation without really grasping how they're used. This is the wrong way to learn a new word.

My personal experience with this was after learning a pile of N3 words. They kept slipping from my brain because I'd only seen them in a vacuum8. The solution for this is with context sentences. Instead of learning a single word, use a sentence with the new word in it, where every word except the new word has already been learned. This is also referred to as 'N+1 sentences' in a few language learning methodologies.

Learning it this way is easier, in that you can often guess the meaning from the context. I initially resisted doing this because it felt like 'cheating' and thought I hadn't really learned the word. I was wrong, if anything this more closely matches real life - words are always encountered in context. When do you ever see and need to remember what a single word in isolation means? There's almost zero reason to do it the 'one word way.'

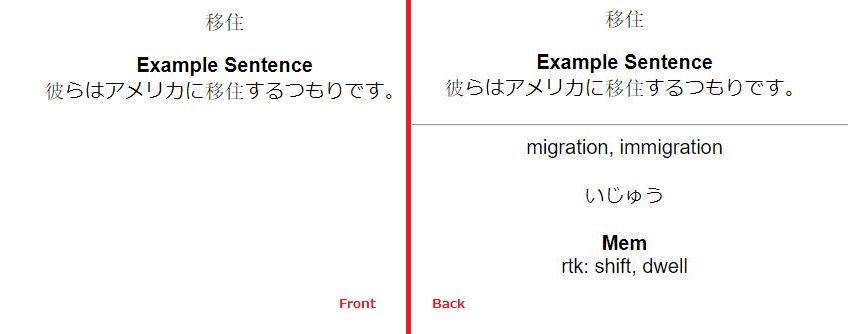

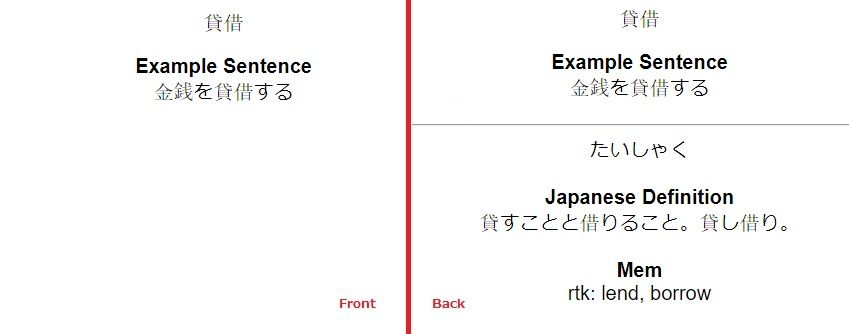

This change to 'learning words in context' also neatly solved another problem I had of words with multiple definitions. For example the word 'lead' can mean the metal, or it can mean the verb 'to lead.' When written by itself you have no idea which meaning is intended. At first I would list all the definitions for a word on the back and try to recite them all, but that got painful fast. Having a contextual sentence on the front means that you can just have one card for each separate meaning. My cards currently look like this:

On the front is the word and a sentence for context, on the back is the definition, pronunciation, and the 'kanji meanings' as taught by RTK (see my earlier post for more info on RTK). More recently, even the definition is in Japanese as well.

9. Using Flash Cards Correctly

As I just mentioned, flash cards are an important tool - but they are only a tool! It can be tempting to catalogue every single word you know into your flash card app (I use Anki) and rely on them too heavily, but that just results in 'Flash Card hell' or 'Anki Hell.' This is a term to describe the situation where you have hours of flash card review per day and spend all your free time on flash cards when you should really be using that time to immerse.

Flash cards are a tool to support your goal of immersing and understanding. They're a very useful tool, which helps rarely used words stay in long term memory, but realise that it isn't immersion and isn't a way to practice fluency. A few tips on how to use flash cards productively:

- Limit adding new words - I restrict myself to an hour of anki per day, max. This works out to about 200 reviews, often done in 5 minute gaps here and there between other things. I only 'learn' new words when that number dips below 150 in a given day.

- Use one-way cards. It can be tempting to have a recall card (Japanese word on the front, english meaning on the back) and a production card, but production cards are not very useful. There are too many possible Japanese words for any given English word and having two cards for one word halves the pace of learning to understand new words encountered in your immersion.

- Use addons - Specifically for Anki, there are addons out there such as the MIA 'Vacation Addon' which allow you to schedule vacation days. Without it, skipping one day results in double the reviews the following day. Use this and other addons to tweak the core algorithm of Anki.

- Tweak the failure penalty (reset interval in Anki). When I fail a word it cuts the interval in half instead of resetting it fully to zero. That helps to address words that just won't seem to stick, without heavily punishing momentary lapses in memory.

- Delete cards. Don't be afraid to delete cards that aren't giving you value. Marie-Kondo that shit out of your life. I do this on a card by card basis but you can even delete your entire Anki deck and start from scratch if it gets too overwhelming. "But won't I forget things!?" Sure, but the words that you really haven't learned can just be added again, and you can use the time you would have spent reviewing こんにちは for the hundredth time on immersion instead. Seeing the word a hundred times through immersion will make it stick better than flash cards ever can anyway!

10. Learning Japanese In Japanese

The last thought I have for this already-too-long post is that as soon as possible, remove English as a crutch. I mention this briefly above and in my previous post on Japanese dictionaries, so I won't dwell on it for long, but the idea is that fluency is impossible as long as you're spending brain cycles on translating to and from English. Not only because you're spending time and energy on the act of mental translation, but because there are many words that don't even have a direct translation.

Just think of the process your brain is going through while you lean on translating to English and back. You hear a Japanese phrase. Translate it to English. Think of your English response. Translate that to Japanese, and finally, speak. It takes too long, it isn't fun, and while it can work in one on one conversation with a patient language partner, you will fall behind in situations like television or group meetings which don't wait for you to keep up.

The only way to native fluency is to think and respond directly in the target language. This is the goal of using a monolingual dictionary and of immersion - to put yourself into environments where you can receive and output the target language. Eventually you'll cut out the intermediate translation step and shortcut directly to and from 'mental-ese', the language-less representation of ideas and meaning in your head.

Hope some of these were useful! I found it a really interesting exercise to reflect back on what I've learned. At this stage I feel like I've got a good handle on the 'how' of learning a language and that the rest of my study is mostly just executing on the same strategy. I'm sure that feeling is totally wrong though and look forward to reflecting in another year to see what else I've learned.

- Note that visual media - manga, film, anime - are particularly good for this because when you dont understand a sentence, the visual aspect provides some clues to the meaning. ↩

- i.e. thousands of hours ↩

- French, Italian, and Spanish ↩

- There is a rule! That most native speakers never learn. According to The Elements of Eloquence the adjective order rule is opinion-size-age-shape-colour-origin-material-purpose. That's why the phrase "lovely little old rectangular green French silver whittling knife" sounds ok but - try it yourself - swap any two of those adjectives and it 'feels' wrong. ↩

- Global warming ↩

- Population aging and declining birth rates ↩

- Smartphone ↩

- Drilling constantly on words you don't use is a bad idea - if you're struggling on a word, at a minimum delete it until you see it in the real world, or find some sample sentences for context. ↩